Investigating an ‘incidental’ arrhythmia

By Dr Ellie Duffy

VVS Commercial Manager

Lottie, a five-year-old female neutered Visla, presented to her primary care vet with an acute right hindlimb lameness, and a suspected cruciate ligament injury. The rest of her clinical examination was unremarkable, and she appeared seemingly otherwise very fit and well. She was examined under general anaesthesia and stifle radiographs were taken, which confirmed a cruciate ligament rupture. Lottie recovered well from the anaesthesia and orthopaedic surgery was planned for a few days later.

On the day of the surgery, general anaesthesia was induced, and an arrhythmia was promptly picked up on auscultation by the primary care team. This was accompanied by many isolated ventricular premature complexes (VPCs) then seen on the ECG trace.

Lottie had no other clinical signs associated with heart disease, and prior to her acute lameness had good exercise tolerance. Other than her suspected cruciate ligament disease, she was seemingly well. Before proceeding with surgery, her primary care vet discussed with her owner that a cardiac work up would be advisable in the first instance. Surgery was postponed and Lottie recovered normally from the general anaesthesia.

Lottie had a specialist live-guided cardiology work up with VVS specialist Dr Pedro Oliveira. A ventricular arrhythmia was noted during the consultation, but there was no obvious evidence of significant structural cardiac abnormalities on echocardiogram. Cardiac troponin I was recommended to rule out myocarditis, which can cause arrhythmias, and other investigations carried out by the primary care team, including full haematology, biochemistry and electrolytes were also all normal.

An abdominal ultrasound was also recommended despite the normal blood work as VPCs can be caused by non-cardiac systemic disease. This is particularly important in young dogs of a breed like this that are not prone to arrythmogenic cardiomyopathies. It was elected not to proceed with the abdominal ultrasound.

In Lottie’s case a 48-hour Holter monitor was recommended to better assess the frequency and severity of her arrhythmia over a longer period of time, and also help determine if anti-arrhythmic treatment might be indicated in this case. The VVS Holter was fitted in practice by the primary care team, and Lottie’s owners kept an activity diary for 2 days before returning to the practice to have the Holter removed, which was sent back to VVS for interpretation.

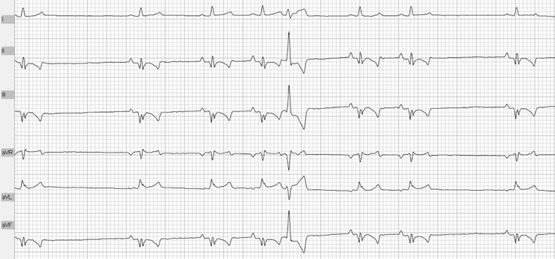

Dr Pedro Oliveira examined the Holter recording and noted frequent ventricular ectopy, with approximately 5000 ventricular premature beats (VPCs) observed. The VPCs occurred generally as isolated premature beats (Figure 1), with a brief example of ventricular bigeminy (Figure 2) and ventricular trigeminy. The absence of episodes of runs of ventricular tachycardia or ‘R-on-T’ phenomenon (Figure 3) indicate a less haemodynamically significant rhythm disturbance. However, the frequency of the VPCs could potentially lead to cardiac structural changes in the future, a so-called arrhythmia-induced cardiomyopathy, therefore treatment was recommended.

- Ventricular Bigeminy: a rhythm characterised by a normal QRS complex alternating with a VPC – 1 in 2 complexes is a VPC.

- Ventricular Trigeminy: a rhythm characterised by two normal QRS complexes alternating with a VPC – 1 in 3 complexes is a VPC.

- R-on-T phenomenon: when a QRS complex starts on the T wave of the previous complex. The complexes are so close to each other that it’s difficult to say where one ends and the other begins.

Figure 1: Isolated VPCS

Figure 2: Example of Ventricular Bigeminy

Figure 3: Example of ‘R on T’ phenomenon

Lottie’s vet had a follow up cardiology call with VVS specialist Dr Nuala Summerfield to discuss the Holter findings in more depth and formulate a treatment plan. Lottie was subsequently started on Sotalol. Sotalol is a class III anti-arrhythmic drug with some additional beta-blocker effects. This is commonly used in the treatment of ventricular but also in some supraventricular arrhythmias. By using sotalol in ventricular arrhythmias (like in Lottie’s case), the aim is to reduce their severity and their frequency. Sotalol can be used alone or, if needed, also in combination with other drugs.

Lottie also still needed to undergo a general anaesthetic for her orthopaedic surgery. Therefore, her primary care vet had an advice call with VVS anaesthesia specialist Dr Nicki Grint to formulate an anaesthetic plan to appropriately manage her specific cardiac, analgesia and anaesthetic needs. Following Dr Nicki Grint’s recommendations, the anaesthesia was uneventful, and Lottie’s surgery went very well.

Follow-up Holter examinations are essential to assess treatment efficacy. Lottie therefore had a repeat Holter a couple of weeks after starting the anti-arrhythmic therapy. The number of VPCs were significantly reduced: she now had approximately 2200 VPCs, less than half of the 5000 VPCs noted on the initial Holter.

Lottie will likely continue anti-arrhythmic therapy for life, with the efficacy of treatment monitored and adjusted by repeat Holter assessments at regular intervals every 6 to 12 months. This will allow any changes to be picked up and managed early to hopefully allow Lottie a full and normal life.

Lottie is so lucky her primary care vet picked up on her abnormalities and had VVS on hand to provide specialist multi-disciplinary support in the comfort of her normal practice. We wish her all the best!

Arrhythmias – incidental or otherwise can feel overwhelming to deal with in general practice, but VVS’ friendly world-class cardiologists are on hand to support you. Working together you can offer outstanding clinical care and reassurance to your patients and their owners.

Get in touch to speak to us further about trying this unique service in your practice!